TOMORROW’S FASHIONS – LIBRARY ELECTRONICA 1972-1987.

Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987.

Label: Ace.

Format: CD.

Release Date: 28th June 2024.

Over the last few years, there’s been a resurgence of interest in library music, with British and European record labels releasing lovingly curated compilations that are welcomed by a coterie of musical connoisseurs who have a passion for library music. This includes DJs, producers and record collectors who are willing to pay large sums of money to add original copies of rare releases to their collections of library music.

However, not everyone can afford to buy original copies of library music rarities. Instead, they buy reissues and compilations that are released on a regular basis.

On 28th June 2024, Ace will release a new compilation of library music, ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987.’ It was compiled by Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne, and has twenty-eight tracks from the Bruton Music, Chappell, De Wolfe, Parry Music and Sylvester music libraries. These tracks were recorded between 1971 and 1987 by some of the giants of library music, including John Cameron, Alan Hawkshaw and Simon Park. They’re responsible for some of the most collectable and rare albums of library music.

Many British collectors of library music started off collecting releases by labels like KPM, De Woife, Amphonic, Bruton Music, Chappell, Conroy and Sonoton from the sixties, seventies and eighties. This is regarded by many collectors as a golden age for library music. However, albums of library music were never meant to fall into the hands of collectors.

Originally, library music was meant to be used by film studios or television and radio stations, and was never meant to be commercially available. The music was recorded on spec by music libraries who often hired young unknown composers, musicians and producers. This ranged from musicians who were known within publishing circles, to up-and-coming musicians who later, went onto greater things, and look back fondly at their time writing, recording and producing library music. This they now regard as part of their musical apprenticeship.

For the musicians hired to record library music, their remit was to supply music libraries with a steady stream of new music, which was originality referred to as production music. During some sessions, the musicians’ remit was write and record music to match themes or moods. This wasn’t easy, but after a while, they were able to this seamlessly. Soon, the musicians were able to enter the audio and write and record a piece of music that matched a theme or mood for a film or television show.

For many young musicians library music was a way to “learn their trade” while making money. It would stand them in good stead. Soon, they became versatile and talented musicians who were capable of switching between genres and moods. This included the musicians hired by KPM Music in the mid-sixties.

When Robin Phillips joined KPM Music in the mid-sixties, he proved to be an astute and visionary businessman. Two decisions he made demonstrated this. His first decision was that KPM Music should switch from the old 78 records to the LP. This made sense as this was what people were buying. They were less prone to breakage, which meant less returns and more profit. LPs could also contain more music, and be released in limited editions of 1,000. The other decision he made was to hire the best young British composers and arrangers.

Among the composers Phillips hired were Keith Mansfield and Johnny Pearson. He spotted their potential, and hired them before they had established a reputation. Many were known within music publishing circles, but not as artists or producers. Later, Phillips hired jazz musician John Cameron, Syd Clark, Alan Hawkshaw and Alan Parker. Their remit was to provide him with new music, which was referred to as production music or library music.

The remit for the new composers and musicians hired by KPM was to write music to match themes or moods. This wasn’t easy, but they were able to do so. Soon, they were creating music that became the themes for TV shows, cartoons and films. For these composers and musicians, they were now part of one of the most lucrative areas of music.

EMI realised that KPM Music had one of the best and most profitable music libraries, and decided to buy the company. While EMI spotted the profitability of KPM Music and the consistency, quality and depth of its back catalogue. However, not everyone approved of library music.

Other songwriters looked down on writers of library music. Nor was the British Musician’s Union a fan of library music. They banned their members from working on recording sessions of library music.

Somewhat shortsightedly, the Musician’s Union thought that eventually, there would come a time when there was no need for any further recordings. Their fear was that the sheer quantity of back-catalogue would mean no new recordings would be made, and their members would be left without work.

To get round the ban, KPM Records flew composers, arrangers and musicians to Holland and Belgium, where local musicians would join them for recording sessions. This meant that often, the same musicians would play on tracks for several composers.

It was only in the late seventies, that the Musician’s Union lifted their ban on new recordings of library music. By then, the golden age of library music was almost at an end. The Musician’s Union ban had cost their members dearly.

Once these tracks were recorded, KPM Music, would release albums of library music. Again, KPM Music were innovators. They’d release limited editions of albums. Often, only 1,000 albums were released. Nowadays, many of these albums are rarities and copies change hands for huge sums of money. That was all in the future.

Once library music was recorded, record libraries sent out demonstration copies of their music to advertising agencies, film studios, production companies, radio stations and television channels. If they liked what they heard, they would license a track or several tracks from the music libraries. That was how it was meant to work.

Sometimes, copies of these albums fell into the hands of record collectors, who realising the quality of music recorded by these unknown musicians, started collecting library music. However, it always wasn’t easy to find copies of the latest albums of library music. That was until the arrival of the CD.

Suddenly, record collectors and companies across Britain were disposing of LPs, and replacing them with CDs. It didn’t matter that the prices of LPs were at all-time low, some record collectors just wanted rid of their collection that they were replacing with CDs.

With people literally dumping LPs, all sorts of musical treasure was available to record collectors. This included everything from rare psych and progressive rock right through to albums of library music. These albums were often found in car boot sales, second hand shops and charity for less than a skinny latte macchiato.

This was the case throughout the period that vinyl fell from grace, and suddenly, it was possible for collectors of British library music to add to their burgeoning collections. Gradually, longtime collectors of library music had huge and enviable collections and were almost running out of new music to collect. Some collectors decided to see what European library music had to offer.

Now these collectors had a whole continent’s worth of library music to discover. Some collectors were like magpies buying albums from all over Europe, while others decided to concentrate on just one country or company. Although it was more expensive to collect European library music, gradually, enviable new collections started to take shape. This included French, German and Italian library music which was recorded during the sixties and seventies.

Later, sample hungry hip hop producers who dug deep into the crates found albums of library music. This was the ‘inspiration’ that they were looking for, and many ‘borrowed’ samples from their newfound musical treasure. Soon, other producers, DJs and collectors went in search of long-overlooked albums of library music.

Some decided to head East. They’ve spent time tracking down library music recorded in Eastern Europe during the sixties and seventies. After the fall of Communism, it was easier to find what for many DJs, producers and collectors was their holy grail.

Since then, library music has become increasingly collectable, with producers continuing to sample them, while DJs incorporate library music into their sets. It’s also big business, with record labels reissuing rare and classic albums of library music and releasing compilations. This includes ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987.’

Opening the compilation is ‘Coaster’ from Simon Park’s album ‘High Climber.’ It was released by De Wolfe in 1982. Bubbling synths play their part in a laidback, relaxing, and summery-sounding cinematic track.

‘Rippling Reeds’ featured on Wozo’s 1979 album ‘Power Source.’ It was also released on De Wolfe, and is a spacious and ruminative sounding track. ‘Atomic Station’ a dark, moody and futuristic track also featured on the album.

John Cameron’s was one of the doyens of library music. Two albums her recorded for KPM Music, ‘Jazzrock’ and ‘Voices In Harmony’ are now regarded as genre classics. However, in 1985 his Explorer album was released by Bruton Music. It opens with Northern Lights-1, a where cascading and rippling synths are part a celestial symphony. Another of ‘Explorer’s’ highlights was ‘Infinity,’ a slow, dreamy and cinematic slice of library music from one of its finest practitioners.

In 1979, Rubba recorded the album ‘Push Button’ for De Wolfe. The seventeen slices of progressive and futuristic electronic music. This included ‘Space Walk,’ one of the album’s highlights.

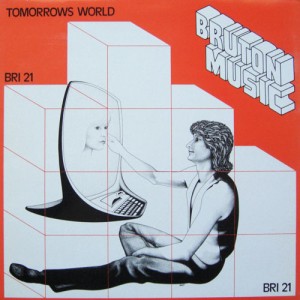

Geoff Bastow’s album ‘Tomorrows World was released on Bruton Music, in 1982. It featured ‘Tomorrow’s Fashion,’ a slow, thoughtful slice of early-eighties library electronica.

Trevor Bastow was session keyboardist who played on Culture Club’s ‘Kissing To Be Clever’ and Paul McCartney’s ‘Give My Regards To Broad Street.’ Later, he wrote the theme to the TV program Keep It In The Family. In 1979, Bastow and Nick Ingham released ‘Life Of Adventure/Video Techniques’ on Bruton Music. ‘Video Techniques’ meanders along gradually, slowly revealing its secrets and showcasing Bastow’s talents.

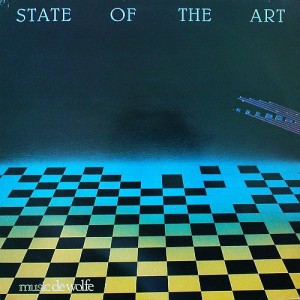

Unit 9 released their ‘State Of The Art’ album on De Wolfe, in 1984. The album saw the group successfully fuse synths and brass. However, ’Optics’ combines elements of eighties synth pop and electronic music to create a dancefloor friendly track.

Warren Bennett came from a musical family. His father Brian was the drummer in The Shadows. The Bennetts collaborated on the 1985 album ‘In The Groove,’ which was released by Bruton Music. ‘Planned Production’ is a truly memorable mid-tempo track that’s a fusion of funk, pop and dubby mid-eighties’ electronic music.

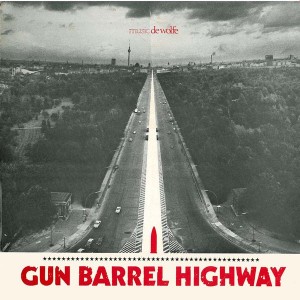

Soul City Orchestra was another of Simon Park’s projects. In 1978 the Orchestra released the album ‘Gun Barrel Highway’ on De Wolfe. It featured the cinematic and elegiac sounding track, ‘Eagle.’

Library music is just part of the Alan Hawkshaw story. He was a pianist, composer and producer who worked with everyone from David Bowie, Olivia Newton-John and Cliff Richard to Donna Summer and Madeline Bell. However, from the late-sixties to the eighties Hawkshaw recorded many albums of library music. This included ‘Frontiers Of Science’ in 1979, which was released by Bruton Music. Two tracks from the album are included. The first is ‘Astral Plain,’ where rippling and cascading synths play their part in the sound and success of this atmospheric and dramatic soundscape. By contrast, ‘Eternity’ is a quite ruminative and timeless sounding track that encourages reflection.

Closing ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987’ is ‘Morning Dew’ by Andy Grossart and Paul Williams. It’s a track from the 1986 album ‘Elements/Weather’ that was released by Chappell. Elements of ambient and new age music combine to create a quite beautiful pastoral sounding track.

For anyone with even a passing interested in library music, ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972- 1987’ is going to be of interest to them. Unlike many previous compilations of library music, it focuses on electronic sounding tracks.

By 1972, synths were becoming more commonplace, and were used to produce music that had an experimental, futuristic, space-age and sci-fi sound. The various library music companies wanted composers and musicians to produce music that was groundbreaking, inventive and innovative. If they did, their music would be licensed for use in film, `TV and adverts. That was what the library music companies were aiming for.

So between 1972 and 1987, composers and producer produced everything from electronica and synth pop to ambient and new age. Sometimes, they combined elements of funk, jazz, pop and disco with synth pop and electronic music. The musicians who recorded the albums were versatile and able to seamlessly switch and combine disparate musical genres. Proof of that can be heard on ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972- 1987.’

For newcomers to library music, ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972 – 1987’ is the perfect primer. It’s an introduction to electronic sounding library music, and covers part of the golden age of library music.

The golden age of library music began in the late-sixties and lasted until the eighties. During that period, music libraries like KPM, De Woife, Amphonic, Bruton Music, Chappell, Conroy and Sonoton released some of the best library music. Many of these album are now rarities that change hands for large sums of money. However, some are still affordable, it’s still possible to find a rarity at a bargain price. For most music fans, the easiest and cheapest way to discover the delights of library music is via compilations like ‘Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972 – 1987.’

Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987.

- Posted in: Ambient ♦ Electronic ♦ Funk ♦ Jazz ♦ Pop ♦ Soul

- Tagged: Alan Hawkshaw, Amphonic, Bruton Music, Chappell, Conroy, De Woife, John Cameron, KPM, Simon Park, Sonoton, Sylvester, Tomorrow’s Fashions - Library Electronica 1972 - 1987, Warren Bennett